A few nice Weight loss images I found:

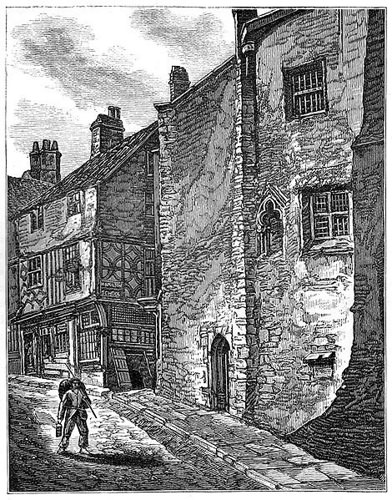

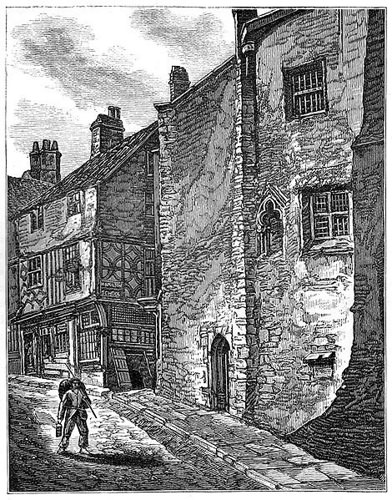

TALES FROM NEWGATE BRISTOL

Image by brizzle born and bred

Newgate Gaol stood in the angle between Fairfax street and Castle Mill street. It was famous as the prison of the early Quakers, the Nonconformists and the poet Savage. Mention is made of prisoners in this gaol as early as 1148. It was rebuilt in 1691 by a rate of sixpence in the £ upon the inhabitants.

‘The Pit to which you descend by eight steps, is 17 feet in diameter, and 8 feet 6 inches high. It has barrack bedsteads, with beds of straw in canvass; and some benevolent Gentlemen of the City occasionally send a few rugs.

‘This dreary place is close and offensive; with only a very small window, whose light is merely sufficient to make darkness visible. In the year 1801, it was chiefly appropriated to convicts under sentence of transportation. Seventeen prisoners are said to have slept here every night!

1734

Bristol, Sep 14. THOMAS KITCHINGMAN, a Scotchman, SAMUEL OWEN, and THOMAS BADGER, three centinels belonging to Col. Montague’s Regiment, lately in quarters here, were indicted for murdering ROGER BARON, who kept a little shop near the Pithay Gate, by striking him on the left side of the head, and thereby fracturing his skull, of which wound he died on the spot, when KITCHINGMAN was found guilty of the murder, and OWEN and BADGER of manslaughter.

Also in Newgate was MARTHA MORGAN, for the murder of her female bastard child, by strangling it with a small cord, and throwing it into a bog house, of which she was found guilty. Sentenced to death.

Sep 27. Yesterday about 11 o’clock in the forenoon, THOMAS KITCHINGMAN, and MARTHA MORGAN, were drawn from Newgate in a mourning coach with four horses, the the place of execution on St Michael’s Hill, attended by a Divine, the Sheriff, and all the City Constables, and a Great Concourse of People; before the coach went a cart with their coffins.. They behaved with much penitence; but KITCHINGMAN denied to the very last his being guilty of the murder he was about to suffer for, affirming, that OWEN (indicted with him for the same fact) was the man that gave the deceased the fatal blow.

MARTHA MORGAN confess’d the murdering her female infant; and after about an hour’s respite for their devotion, the cart drew away. The day before their execution, MARTHA MORGAN sent a very melancholy letter to the father of the child.

Four soldiers took care of the body of KITCHINGMAN, and convey’d it to St Michael’s Churchyard, where after being put in the ground, they put lime into the coffin, and pour’d water upon it, to prevent the surgeons stealing the body; and the woman’s body was deliver’d to her brother.

1737

Bristol, Jul 23. This week was committed to Newgate Gaol BENJAMIN YOUNG, a little deformed Lad about 16 years of age, for the wilful murder of JAMES WEBB, an Infant about 20 months old, by throwing it into the River Avon, by which it was drown’d. It seems he is noted for trying experiments on children in the hanging way, and that not long ago he had like to have made an end of two children in this branch of the art; one of whom he ty’d up with twine, which with the struggling of the child stript the skin off the underjaw.

The Body was taken up at Rownham Passage on Wednesday or Thursday last, and three persons have swore to the fact. Various are the conjectures on this murder; some being of opinion that he cannot be convicted on account of his age; but he would be of age to be convicted; for the Law says, (vide Judge Hall’s Pleas of the Crown) That if a child of ten years old shall kill a man, it’s not death; but if he shall kill one younger than himself, that then in such case he shall be convicted, and suffer death as in all other cases of felony.

1738

Bristol, Oct 28. Sunday night last a most shocking murder was perpetrated by one WILLIS, (who kept a Huckster’s shop outside Lawford’s Gate, and sold spirituous liquors) his wife, and one BETTY DARBY, on the body of EDWARD FINKS; belonging to the brass works at Baptist Mills. They are now both in Newgate awaiting execution for this horrid fact.

1740

Bristol, Dec 29. The beginning of this week a soldier was committed to Newgate for the murder of a child, by striking it with a large stick when in the arms of its father as he pass’d along the Street.

Bristol, Nov 22. One day this week the body of a match woman was found in the mud in Bristol harbour, cut and mangled in a most barbarous manner, suppos’d to be done by a blackman belonging to a ship, who was seiz’d near the bridge with a bloody hammer about him, and was committed to Newgate on a violent suspicion of his being the perpetrator of so horrid a deed.

Bristol, Dec 20. One Day this week a poor woman perish’d with the cold in the Horse Fair. She was almost naked, and was pelted with snow balls a little before she died by a group of wicked boys; – the unhappy effect of a loose education, and a reproach to their parents and friends, they were committed to Newgate Gaol for 21 days.

1743

Bristol, Feb 12. Yesterday morning one MARTHA WHITE was apprehended, and carried to St Peter’s Hospital, on a violent suspicion of murdering her two bastard children, which she was deliver’d of in a Necessary House, in the back lane behind the Old Market, On Wednesday last, and being found there on Thursday night. The Jury sat on the bodies Friday evening, and brought in their Verdict Wilful Murder. She was committed to Newgate Gaol to await execution. The usual experiment was made on swimming the lungs of the children, by which it appear’d one of them was born alive, and the other dead.

May 3. Bristol, Apr 30. Newgate Goal account of Press Gang; member killed by an ALEXANDER BROADFOOT, found guilty by a Coroner’s inquest, but taken on ship. Charged with the murder of CORNELIUS CALLAHAN, found guilty of manslaughter, burnt in the hand.

Bristol, Oct 19. Highwayman THOMAS TUCKER held-up a tinker and his wife on London Road. He is held in Newgate on suspicion of murdering the poor woman, in one of his pockets were found two fingers, which he had cut off the hands of the deceased for the sake of her rings.

Dec 24. Last Tuesday ANDREW BURNET and HENRY PAIN, two foot soldiers, were brought from Gloucester Castle to Newgate Bristol for execution, for the murder of RICHARD RUDDLE, late coachman to Sir ROBERT CANN, and robbing him of his watch & chain, the watch was later found in the possession of the said BURNET.

And on Thursday, HENRY PAYNE and ANDREW BURNET were executed at Durdham Down, on the Rocks, above the Hot Well: They were both very penitent, and own’d up to the robbery and murder of Sir ROBERT CANN’S coachman, tho’ they said it was not their intent to have kill’d him; but he being a stout resolute man, BURNET gave him the unhappy blow that occasion’d his death. They are likewise in chains.

Apr 28. Last Friday night the bodies of HENRY PAYNE, and ANDREW BURNET, (who were executed for the murder of Sir ROBERT CANN’S coachman) were stolen off the gibbet on Durdham Down; but have since been found among the rocks, and hung up again.

1746

Bristol, Jan 25. Saturday last in the afternoon was committed to Newgate, JOHN BARRY, who kept the Harp and Star public house on Bristol Harbour, On a violent suspicion of poisoning one JAMES BARRY, a sailor, and an officer of the Duke Privateer (whom he invited and got to his house, where he died in a short time after) for forging his will, in company with one P HAYNES, an attorney, (whom he kept in his house for drawing Seaman’s Wills) and a servant boy of his own and swearing to the said Will himself. It seems the deceas’d was entitled to near £2000 prize money. HAYNES and the Boy are both confin’d in Bridewell. BARRY was taken out of his own House by the sheriffs of the city in person, attended by their officers, where he had conceal’d himself under his bed.

1800

"Hanged on the Gallows" Dick Boy’ from Oldland Common

KINGSWOOD HOT- BED OF CRIME

After the loss of their commons, petty theft or highway robbery became almost the only way by which Kingswood colliers could add to their starvation wages, in spite of the harsh penalties which might be incurred. It is to be remembered that in the year 1800 a man could still be condemned to execution for such minor offences as picking a pocket or stealing goods over the value of 6/- from a shop. Undeterred by these heavy sentences, hungry men turned to petty larency or house-breaking mainly to obtain the necessities of life.

Two examples, amongst many others in contemporary newspapers, or legal records, will serve as illustration:—In 1795 ‘ Two well-known characters of the Parish of St. George, under cover of legal authority, entered the house of a poor woman with intent to take away her bed. Her neighbours seized the offenders and conveying them to one of the deepest pits of the neighbourhood, there left them where they have been for three days without other food than bread and water.’

In May, 1800:— ‘ Thos. Hill, returning from Bristol market to Bath was robbed of £1.7s. by two men in smock frocks, this being all the money the poor man had. Not satisfied, the villains stripped him of his coat and waistcoat.’ In acts of law-breaking and violence such as these, the offence was greatly heightened should the culprit resist arrest. Carrying or pointing a gun was punished by transportation; shooting at a constable incurred a sentence of execution with little, if any, chance of a reprieve.

It was this act of desperate defiance in the year 1800 which brought Richard Haynes, alias ‘ Dick Boy,’ to the gallows on St. Michael’s Hill. Local tradition gives Oldland Common in Gloucestershire as his birthplace, or the nearby village of Hanham, and it is here that many stories have gathered round his name, one to the effect that he could readily be recognised by his very large ears; another that he invariably slept with his boots on in order to make a hasty escape. In sober truth, Dick’s real character was not that of a romantic highwayman, but of a common thief and ne’er do well. The story, told in Braine’s ‘ History of Kingswood Forest,’ of his having wounded his father, mistaking him in the darkness for a rich traveller, may have been founded on fact, but no mention was made of it at his trial.

On March 3rd, 1800, Dick appeared at Bristol Assizes before the Recorder, Mr. Vicary Gibbs, on the charge of having stolen a silver tankard. Whilst resisting arrest, he had also fired a pistol at Constable Driver, and at a second unnamed constable. The place where this happened is not given, nor are there any details of Haynes’ previous life and character. It is merely stated that he belonged to the Parish of Bitton and that he had formerly been a collier. At the same Assizes, four other men were also condemned to death for theft, two for stealing salt from a trow at the Quay, and two more for stealing butter from a sloop at the Back. A woman, Phoebe Pitt, was sentenced to execution at the same time for stealing a diamond ring. These last five persons were later all reprieved, but for another criminal. Henry Lane, ‘ who issued Bank of England notes knowing them to have been forged,’ the sentence remained. Later on, Lane, too, received ‘ a respite during His Majesty’s pleasure.’

AWAITING DEATH IN NEWGATE GAOL

Only one prisoner now remained, and for two weary months Haynes was left waiting for death in the ‘ Pit ‘ of Newgate Gaol, the prison which stood near the bottom of what is now Narrow Wine Street. The river Froom then flowed down Broadmead and between the water and the prison there only stood one building, that of an evil’ smelling glue factory. The Pit was the underground dungeon of the prison, eighteen steps below ground level; it was reserved for condemned criminals and for convicts awaiting transportation. Here, in a room only 17 feet square, reeking of filth, seventeen prisoners slept every night, with no bedding except a foul canvas mattress stuffed with straw. ‘ Some benevolent gentlemen of the city occasionally sent a few rugs.’ The floor of this cell at river level was always damp, and for ventilation there was only one tiny window, the chimney being permanently boarded up and the door at the top of the stairs closed night and day.

In the rest of the gaol, as well as in the Pit, everyone was idle, all types of criminals, both men and women, being herded together during the day, ‘ filthy, mutinous and made desperate by suffering and hunger.’ The only food provided daily was a 3d. loaf weighing just under 1Ib., and for this even the poorest had to pay the jailer, Mr. Humphries, 10d. per week, while the better-off prisoners paid as much as 2/6d. A collecting-box outside the prison gates silently begged for donations from the charitable who at irregular intervals sent gifts of potatoes, beef, herrings, vegetables and coal for the almost starving inmates.

In spite of this, men who entered the prison as healthy human beings, in a few months became emaciated and dejected. An accused man might wear heavy leg-irons for nearly a year whilst awaiting his trial at the annual assize. In 1815 J. S. Harford, the philanthropist of Blaise Castle, who was also a reformer of Kingswood, himself saw ‘the irons put upon a little boy 10 years old, brought in for stealing 2 lbs. of sugar.’ Weakened by conditions such as these, many prisoners died of gaol fever, some from small’pox and some apparently from sheer starvation. At the end of two months in the Pit, in these terrible surroundings, the day for Dick Boy’s execution arrived.

Execution up the steep slope of St. Michael’s Hill

On the preceding night he was attended from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. by Mr. James Bundy, ‘ a gentleman belonging to the late Mr. Wesley’s Society ‘ and also by Mr. Walcam, the prison Chaplain, who both tried ‘ to comfort his soul.’ When morning came his cell door opened, and, guarded by soldiers, he was marched off to the open cart standing outside the prison gate. From. this point he was driven through the streets of Bristol, which were lined with jeering and yelling crowds, and up the steep slope of St. Michael’s Hill. Mr. Bundy, the compassionate Wesleyan, went with him in the cart ‘ and as they passed through the streets they sang hymns together and prayed.’

It was a cold, showery April day, so that, while Dick stood waiting on the scaffold with the rope round his neck, the prison chaplain only made a short speech to the eagerly expectant crowd, who on these occasions were always dressed in their best clothes. It is probable that a pamphlet describing Hayne’s life and last confession was being sold to the multitude during their long wait before-hand. Some spectators had been waiting even before the dawn broke over the Downs. ‘ After Mr. Walcam’s speech ended, and the cap had been drawn over the face of the criminal, the chaplain gave him the last embrace which he received with the utmost tenderness.’

An entry in the ‘ Bristol Journal ‘ for April 26th, 1800 records that ‘ At the fatal tree Haynes behaved with the utmost penitence. He made no address to the surrounding multitude, as he seemed too absorbed in thought.’ The execution having taken place, the body ‘ after hanging for the usual time’ was conveyed in a hearse and deposited in the crypt of St. Michael’s Church, later being buried in the churchyard there. Executions such as this took place on St. Michael’s Hill during the next twenty years, until, in 1820, Newgate Gaol was replaced by one newly built on the New Cut, the entrance gate of which still stands near Gaol Ferry.

From that date, the condemned prisoners were hanged on a gallows erected over the entrance gate of the gaol itself. Here, Just before an execution, official notices had to be posted, by order of the prison Governor, to warn the crowds, sometimes numbering as many as 20,000 spectators, to beware of the possible collapse of the bridges and banks under so great a weight. This gaol, with its tread’wheel for raising water, was replaced, in its turn, by the one at Horfield in 1883, so that soon the story of the old gallows on St. Michael’s Hill, and Dick Boy’s public execution there, faded from men’s minds, or became only a faint memory of a more barbarous age.

Memorial Day Service at Old St Paul’s, Wellington – May 30, 2011.

Image by US Embassy New Zealand

Memorial Day Service at Old St Paul’s, Wellington – May 30, 2011.

Related:

Remarks by the President at a Memorial Day Service

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington, Virginia

11:25 A.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you. Thank you so much. Please be seated.

Thank you, Secretary Gates, and thank you for your extraordinary service to our nation. I think that Bob Gates will go down as one of our finest Secretaries of Defense in our history, and it’s been an honor to serve with him. (Applause.)

I also want to say a word about Admiral Mullen. On a day when we are announcing his successor as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and as he looks forward to a well-deserved retirement later this year, Admiral Mullen, on behalf of all Americans, we want to say thank you for your four decades of service to this great country. (Applause.) We want to thank Deborah Mullen as well for her extraordinary service. To Major General Karl Horst, the commanding general of our Military District of Washington; Mrs. Nancy Horst; Mr. Patrick Hallinan, the superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery, as well as his lovely wife Doreen. And to Chaplain Steve Berry, thank you for your extraordinary service. (Applause.)

It is a great privilege to return here to our national sanctuary, this most hallowed ground, to commemorate Memorial Day with all of you. With Americans who’ve come to pay their respects. With members of our military and their families. With veterans whose service we will never forget and always honor. And with Gold Star families whose loved ones rest all around us in eternal peace.

To those of you who mourn the loss of a loved one today, my heart breaks goes out to you. I love my daughters more than anything in the world, and I cannot imagine losing them. I can’t imagine losing a sister or brother or parent at war. The grief so many of you carry in your hearts is a grief I cannot fully know.

This day is about you, and the fallen heroes that you loved. And it’s a day that has meaning for all Americans, including me. It’s one of my highest honors, it is my most solemn responsibility as President, to serve as Commander-in-Chief of one of the finest fighting forces the world has ever known. (Applause.) And it’s a responsibility that carries a special weight on this day; that carries a special weight each time I meet with our Gold Star families and I see the pride in their eyes, but also the tears of pain that will never fully go away; each time I sit down at my desk and sign a condolence letter to the family of the fallen.

Sometimes a family will write me back and tell me about their daughter or son that they’ve lost, or a friend will write me a letter about what their battle buddy meant to them. I received one such letter from an Army veteran named Paul Tarbox after I visited Arlington a couple of years ago. Paul saw a photograph of me walking through Section 60, where the heroes who fell in Iraq and Afghanistan lay, by a headstone marking the final resting place of Staff Sergeant Joe Phaneuf.

Joe, he told me, was a friend of his, one of the best men he’d ever known, the kind of guy who could have the entire barracks in laughter, who was always there to lend a hand, from being a volunteer coach to helping build a playground. It was a moving letter, and Paul closed it with a few words about the hallowed cemetery where we are gathered here today.

He wrote, “The venerable warriors that slumber there knew full well the risks that are associated with military service, and felt pride in defending our democracy. The true lesson of Arlington,” he continued, “is that each headstone is that of a patriot. Each headstone shares a story. Thank you for letting me share with you [the story] about my friend Joe.”

Staff Sergeant Joe Phaneuf was a patriot, like all the venerable warriors who lay here, and across this country, and around the globe. Each of them adds honor to what it means to be a soldier, sailor, airman, Marine, and Coast Guardsman. Each is a link in an unbroken chain that stretches back to the earliest days of our Republic — and on this day, we memorialize them all.

We memorialize our first patriots — blacksmiths and farmers, slaves and freedmen — who never knew the independence they won with their lives. We memorialize the armies of men, and women disguised as men, black and white, who fell in apple orchards and cornfields in a war that saved our union. We memorialize those who gave their lives on the battlefields of our times — from Normandy to Manila, Inchon to Khe Sanh, Baghdad to Helmand, and in jungles, deserts, and city streets around the world.

What bonds this chain together across the generations, this chain of honor and sacrifice, is not only a common cause — our country’s cause — but also a spirit captured in a Book of Isaiah, a familiar verse, mailed to me by the Gold Star parents of 2nd Lieutenant Mike McGahan. “When I heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?’ And I said, ‘Here I am. Send me!”

That’s what we memorialize today. That spirit that says, send me, no matter the mission. Send me, no matter the risk. Send me, no matter how great the sacrifice I am called to make. The patriots we memorialize today sacrificed not only all they had but all they would ever know. They gave of themselves until they had nothing more to give. It’s natural, when we lose someone we care about, to ask why it had to be them. Why my son, why my sister, why my friend, why not me?

These are questions that cannot be answered by us. But on this day we remember that it is on our behalf that they gave our lives — they gave their lives. We remember that it is their courage, their unselfishness, their devotion to duty that has sustained this country through all its trials and will sustain us through all the trials to come. We remember that the blessings we enjoy as Americans came at a dear cost; that our very presence here today, as free people in a free society, bears testimony to their enduring legacy.

Our nation owes a debt to its fallen heroes that we can never fully repay. But we can honor their sacrifice, and we must. We must honor it in our own lives by holding their memories close to our hearts, and heeding the example they set. And we must honor it as a nation by keeping our sacred trust with all who wear America’s uniform, and the families who love them; by never giving up the search for those who’ve gone missing under our country’s flag or are held as prisoners of war; by serving our patriots as well as they serve us — from the moment they enter the military, to the moment they leave it, to the moment they are laid to rest.

That is how we can honor the sacrifice of those we’ve lost. That is our obligation to America’s guardians — guardians like Travis Manion. The son of a Marine, Travis aspired to follow in his father’s footsteps and was accepted by the USS [sic] Naval Academy. His roommate at the Academy was Brendan Looney, a star athlete and born leader from a military family, just like Travis. The two quickly became best friends — like brothers, Brendan said.

After graduation, they deployed — Travis to Iraq, and Brendan to Korea. On April 29, 2007, while fighting to rescue his fellow Marines from danger, Travis was killed by a sniper. Brendan did what he had to do — he kept going. He poured himself into his SEAL training, and dedicated it to the friend that he missed. He married the woman he loved. And, his tour in Korea behind him, he deployed to Afghanistan. On September 21st of last year, Brendan gave his own life, along with eight others, in a helicopter crash.

Heartbroken, yet filled with pride, the Manions and the Looneys knew only one way to honor their sons’ friendship — they moved Travis from his cemetery in Pennsylvania and buried them side by side here at Arlington. “Warriors for freedom,” reads the epitaph written by Travis’s father, “brothers forever.”

The friendship between 1st Lieutenant Travis Manion and Lieutenant Brendan Looney reflects the meaning of Memorial Day. Brotherhood. Sacrifice. Love of country. And it is my fervent prayer that we may honor the memory of the fallen by living out those ideals every day of our lives, in the military and beyond. May God bless the souls of the venerable warriors we’ve lost, and the country for which they died. (Applause.)

END 11:37 A.M. EDT